Honoring Juneteenth in the Classroom

Juneteenth was absent from my K-12 school experience. The first time I learned about Juneteenth, I was a college sophomore. It was 2002, and I took an “Intro to the African American Experience” course at Florida State University with Dr. Na’im Akbar. In the course, I quickly realized my high school history courses had failed me. Entering college, I had taken AP US History, AP European History, and an International Baccalaureate (IB) history class. It was clear that these courses had been white washed to exclude the rich and complex histories of Black people around the world.

Fast forward to 2019, I was teaching 6th grade and the year culminated with an “Enslavement and Resistance in America” unit. The table below includes the essential questions and enduring understandings for the unit. Note: This curriculum is created by my school district.

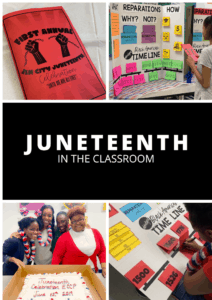

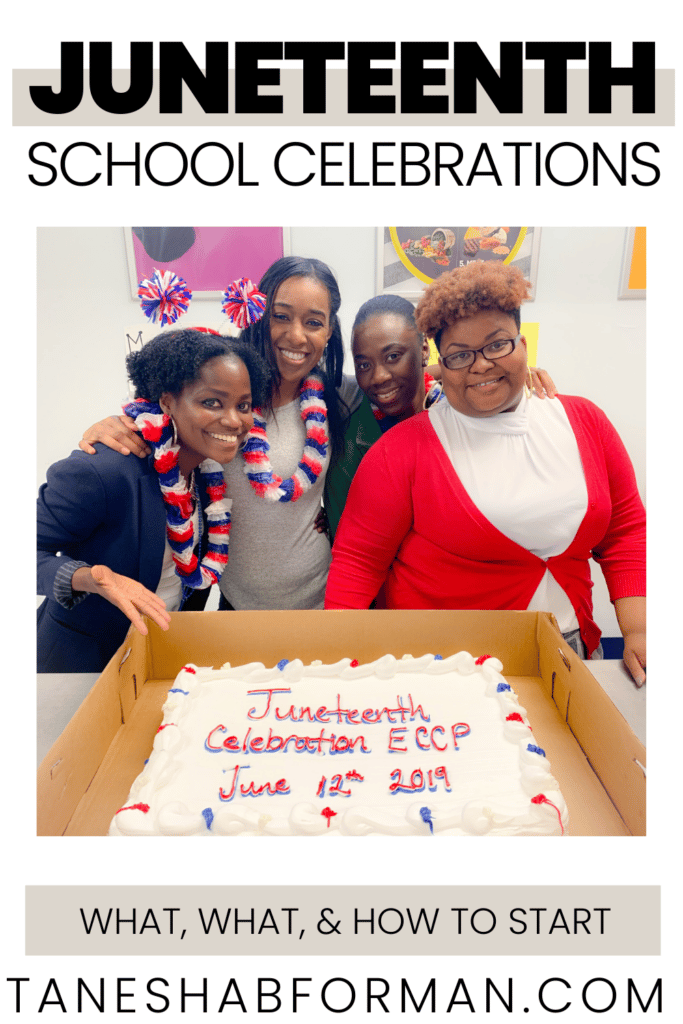

With the frame of the unit set, I looked to bring this unit to life. Juneteenth felt like a perfect match, but I want to bring this to my students. After learning about the Juneteenth and dissecting our unit, students voted to organize our school’s first Juneteenth celebration.

Heading into the 2019-2020 school year, I had big plans for Juneteenth. We were going to celebrate as a K-8 school and build on lessons learned from the previous year. And then a global pandemic happened. And then the fight for racial equity for Black people was reinvigorated by the murders of Breonna Taylor, George Floyd, and Ahmaud Arbery. I almost gave up on planning Juneteenth, but grounded myself in the reason Juneteenth is so special. This post attempts to provide a few key ideas to consider when hosting a Juneteenth (in-person or virtual) celebration with your school.

Know the History!

This ain’t yo average party. The history of Juneteenth is tied to justice delayed and justice denied for Black people. This history has reigned over the Black, or African American experience in America. The name Juneteenth comes from the date, June 19, when the last enslaved people in Texas were told slavery in the United States was illegal, and enslaved Black people were “free.” When reflecting on justice delayed, the Emancipation Proclamation was effective as of January 1, 1863. On paper, the Emancipation Proclamation ended enslavement. However, word did not spread through the country. On June 19, 1865, Union army General Gordon Granger arrived Galveston, Texas, and read the executive orders that declared all enslaved people free. Celebrations took root and have existed since. Note, the delayed justice. Enslaved people waited more than two years to learn they had been freed.

For 155 years, Black communities (especially in Texas) have celebrated Juneteenth. It’s not a typical barbecue celebration because it acknowledges our past is drenched in racism and oppression. However, it highlights the resilience and accomplishments of Black Americans in our society. It’s a “both/and” event. This was my quick synopsis of Juneteenth, but before implementing it in the classroom, learn about it. Don’t reduce it to the day Black people were “free” because that struggle continues. In learning, consider:

- What is Juneteenth?

- What makes Juneteenth important to Black Americans?

- Which contributions by Black Americans impact my daily life?

- What should white people do to honor Juneteenth?

- What can white people and non Black people of color do to support the Black community?

Below are two videos to get started, but get academic and lean into primary sources.

Let the Students Lead

Our first celebration was driven by a student simply asking, “Why don’t we celebrate that?” after we watched and discussed parts of a Black-ish episode. In that moment, I facilitated a conversation with the students about whether or not they wanted to lead the planning for Juneteenth, and what they would have to commit to to make it happen. The students were with it!

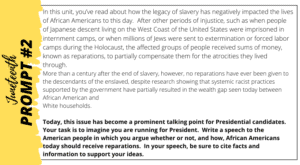

In our first Juneteenth celebration, students completed projects and wrote a speech aligned to the unit. In this way, they knew their work would be shared and that likely increased investment. Given this was our final unit, I worked to ensure students were set up to put their best writing forward. Below are the writing prompts provided by my district:

|

| For prompt #2, I gave students the option of completing a group project on reparations to present to the class. |

In moving the event to the entire school, once again I leveraged the unit we were studying. Our final remote learning unit was Poetry. Therefore, students had a ton of freedom in terms of what they could present during our Juneteenth event. Many of them drew upon the current events of racial justice and police brutality in the Black community that in my opinion aligned with the spirit of Juneteenth.

For the lower grades (K-2). Teachers read the book Juneteenth for Mazie, which is a solid read. It uses the word slave instead of enslaved people, but teachers at my school are equipped to talk this through with the kids (yes, the babies get the truth)! My school purchased this unit from LaNesha Tabb and Naomi O’Brien to use with the book. For the older kids, we presented what Juneteenth is, leveraged videos, and allowed them to explore and research on their own.

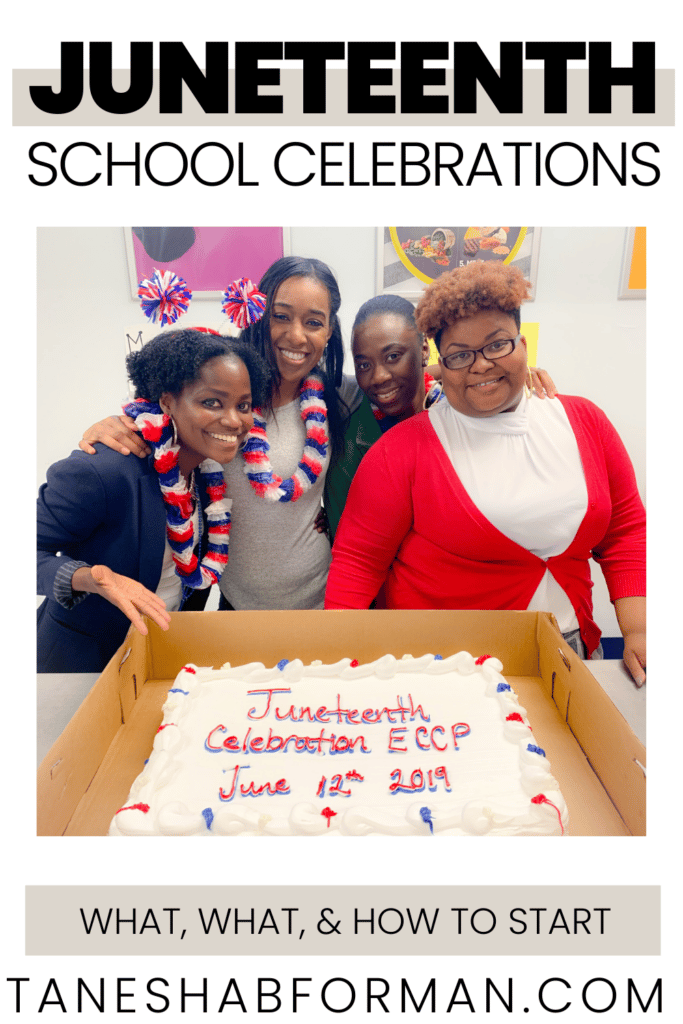

For a school celebration, one strategy is having a theme. Our first year, the theme was “Until We Are All Free” and this year it was “Still Celebrating Freedom.” The theme can help shape the program. Students and teachers submit work for the show and that’s how it is built. It can be as long or short as you want. The first year it was an hour and a half, and the second year (on Zoom) it was about an hour. Below are a few pictures:

Invest the Community

The third big action step is investing the school community. This means other teachers, administrators, and student families. I created a letter for parents requesting donations, but I told the students that it wasn’t mandatory, and they should actually discuss what they were planning with their parents or guardians. I did used the money that my school reimburses teachers for buying supplies. I believe it was $150. My school also donated an additionally $200, which was more than enough to get food from Popeyes (I used my teacher negotiation skills). I took the lead in communicating with our leadership team and other teachers. The first year we had the band and dance teams perform, which required some coordination. Additionally, my team worked to create a special schedule for the day.

With the virtual Juneteenth, we took the same approach. Weeks ahead of the event, I presented Juneteenth to the staff, asked if there interested in participating, and clarified expectations. Given the nature of the internet, we decided to film the performances and put it together in a video in order to account for tech issues.

Lastly, hold space for the team to reflect. Black Americans have contributed so much to this country and have yet to experience “liberty and justice for all.” Below is one of the performers who remixed the National Anthem.

oh say can you seethe Blacks killed in daylightfor too long we waitfor human decencythe flag with red strips and white starsdoes not represent usbut we ask and we ask for too long and we’re tiredthose cops took their airand now the ground burns everywherecus the truth has revealedthat racism is still hereoh say does the bill of rights matter to Blackssay this “land of the free”still holds us in shackles

PIN FOR LATER!

JOIN THE COLLECTIVE

Sign up and access the FREE resources to support your Anti-Bias/Anti-Racism journey.

Tanesha B. Forman

I'm a current middle school administrator who loves breaking down complex topics and providing opportunities for educators learn, reflect, practice, and implement methods that foster equity and anti-racism. I believe we win together!

Behind the Blog

Hi, I'm Tanesha.

I’m a current middle school administrator who loves breaking down complex topics and providing opportunities for educators learn, reflect, practice, and implement methods that foster equity and anti-racism. I believe we win together!